Ever felt confused when a trainer talks about positive punishment and negative reinforcement? You’re left wondering how anything positive can be bad? You’re not alone.

There’s a whole lot of scientific jargon in dog training and understanding positive and negative, reinforcement and punishment can feel like wading through mud. Especially since some of the language has a specific meaning in behaviour terms, but a different meaning in everyday language.

In behaviour science teminology positive doesn’t mean good, negative doesn’t mean bad. Reinforcement isn’t always about giving you dog something they want, just as punishment isn’t always about hurting or intimidating.

Understanding Operant Conditioning Consequences

The terms we use are referring to the consequences applied after the behaviour has occurred. They always happen after the behaviour. If something happens before, then it no longer functions as a consequence.

We use or try to use, consequences to change the likelihood of a behaviour happening again. Consequences always come after the behaviour. That means we can’t change what has already happened. We can only influence what’s likely to happen in the future.

Positive and negative are mathematical terms.

- Positive means that we are adding something to the scenario.

- Negative means we are taking something away.

Something can be added that the learner really likes, such as a delicious treat, or it could be something horrible, like a kick to the chest. Similarly the thing taken away could be something the learner will miss, like the delicious treat, or it could be something the learner wants to stop like your early morning alarm.

The other terms refer to what happens to the target behaviour after the consequence has happened.

- Punishment means the target behaviour decreases.

- Reinforcement means the target behaviour increases.

A behaviour can increase or decrease in:

- frequency – it will happen less often if punished, more often if reinforced

- e.g. barking happens more or less often

- duration – it will happen for less time if punished, or for longer if reinforced

- e.g. barking reduces to one or two short barks, or continues for minutes

- intensity – it will be “smaller” if punished, or “bigger” if reinforced

- e.g. barking gets quieter or louder

What is Positive Punishment?

- Something is added that the learner will want to avoid with the intention of reducing a behaviour.

- Example: Applying a shock or stim through an electric collar after your dog runs away from you.

What is Positive Reinforcement?

- Something is added that the learner will want to access with the intention of increasing a behaviour.

- Example: Giving your dog a treat after they run towards you.

What is Negative Punishment?

- Something is taken away that the learner will want with the intention of reducing a behaviour.

- Example: Removing or withholding the food bowl when your dog gets up from a sit

What is Negative Reinforcement?

- Something that the learner will want to avoid is taken away with intention of increasing a behaviour.

- Example: Stopping the shock when your dog sits.

Here’s a video explaining the four contingencies with multiple examples of each.

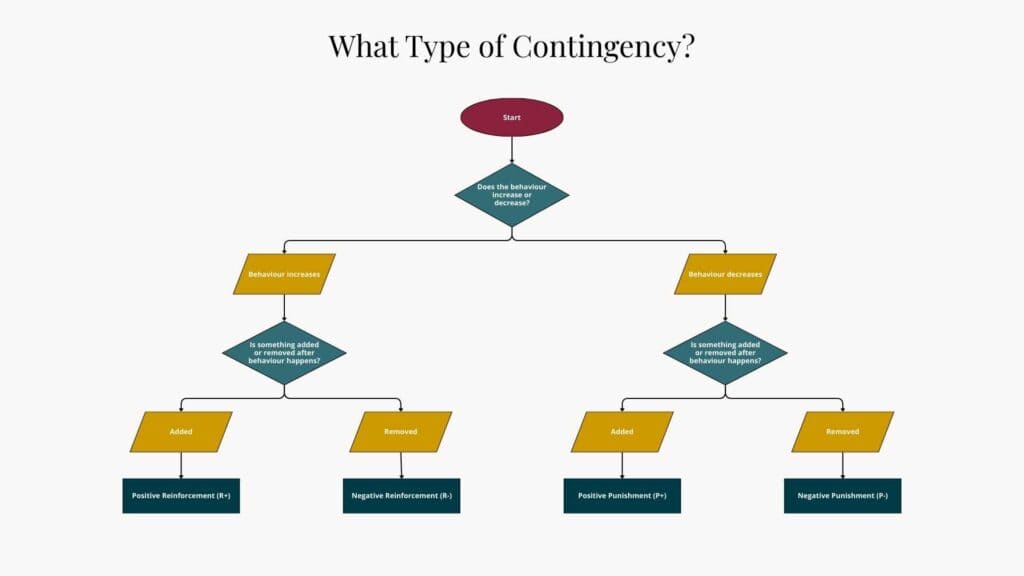

How to Identify a Contingency

- First, ask: Is the target behaviour increasing or decreasing?

- If the behaviour increases it’s reinforcement, if it decreases it’s punishment.

- Then: Was something added or taken away?

- If something was added it’s positive, if it was subtracted it’s negative.

- You may find that the consequence you intended is not what is happening.

- Finally (and most importantly): How is your dog feeling?

- Is their body language indicating that they are enthusiastic and fully engaged with the process?

- Or is their posture lowered, or they aren’t moving much, are they trying to move away and avoid training?

Why We Should Use Positive Reinforcement in Dog Training

Having said that the individual terms positive/negative, reinforcement/punishment don’t mean good or bad the actual contingency in play matters a lot. They aren’t just labels; they help shape the emotional response of the learner. How your dog feels about the situation will often have a lot to do with what consequence you are using.

That’s not to say that any one type of consequence is always good or bad. Life is never that simple. But using the manipulation of something your learner dislikes and will actively try to avoid is going to cause stress, potentially fear and then if they anticipate that same thing happening in the future – anxiety.

Trust = confident expectation of something and implies a feeling of security. As a result our dogs will choose to interact with us more. Dogs who trust will use their behaviour to access reinforcers rather than try to escape situations.

Behaviour always has a purpose. We behave for a reason. Positive reinforcement trainers want our learners to respond to us and their environment because they have the skills and motivation to do so. Not because they are forced to behave in order to avoid or escape punishment.

Common Misunderstandings About Operant Conditioning Terms

Positive punishment sounds like it’s a nice way to stop behaviour.

If we go back to our definitions, the positive part means adding something, while the punishment bit means with the intention of reducing behaviour.

For positive punishment to effectively reduce behaviour, the thing that is added has to be something that the learner will want to avoid. They successfully avoid it in the future by not performing the behaviour.

Typically, adding something to a situation that a dog wants to avoid will cause stress, perhaps even fear, and that’s certainly something we want to avoid.

Shocks or stims are just communication

The basis of using a shock or stim is that it is something your dog will avoid, otherwise it wouldn’t be effective. It might not be long-lasting pain, but it’s pain, nevertheless.

I get static shocks a lot, especially as the weather heats up, and the air gets drier. It’s particularly bad in my office. I’m not sure if it’s the carpet or all the electrical equipment. When the weather gets warmer, I will often get a shock as I touch the wall switch to turn off the light. It gets so bad that by the end of the summer I will hesitate to touch the switch, or even touch my dogs because I so often give them shocks.

It’s not a long-lasting pain, but it makes me quickly withdrawn my hand each time it happens, and it’s enough to make me worried about touching anything.

Look at the dog’s body language to determine how they are feeling about the use of shock. While the dogs may appear obedient and responsive, what is their body posture like? I often see lowered bodies, stiff movements, tails low, ears back, mouths either completely closed and held tight, or wide open with the amount of stress panting.

Compare it to the body language you see when a dog is having a good time.

Whether the dog can perform the behaviour is not the only outcome to be concerned with.

Positive reinforcement always leads to good things.

This is tricky to answer because consequences affect the likelihood of behaviour happening in the future. So really, we can only say if something was reinforcing if that behaviour happens again or more often. Which then means that yes, it was reinforcement.

What we need to be more concerned with is how our learner feels at the time. And this is why how you choose to carry out your desired consequence matters. We’ve already discussed that using something your learner will try to avoid is highly likely to increase stress. What about if we are trying to teach our dog that what they find scary isn’t scary? Is just giving them treats going to fix it? After all it’s positive reinforcement right?

It’s entirely possible to intend to use positive reinforcement, but overall, the experience is still aversive to the learner. For example, using food to lure your dog onto or near something your dog finds scary. It’s common to think of asking strangers to feed your dog a treat will help them feel better about people they don’t know. But what I often see happen is that the dog reaches for the treat – often stretching their neck as far as possible to keep distance – and their body language shows they aren’t confident. Once they’ve taken the treat, now they find themselves too close to the scary person, and the food has gone, so they go back to barking or lunging to make the scary thing go away.

So while we were trying to use positive reinforcement with good intentions, overall this ends up being a bad experience for our dog. At best, it does nothing to help them feel better about people. At worst, it makes people more scary and also makes them wary of food being offered – so now training with food in those situations has been poisoned. What a nightmare.

Using positive reinforcement isn’t enough to ensure your dog feels good during training. We need to think not just about what we’re giving, but how we’re giving it. And whether our dog feels safe and in control throughout.

Get help from professionals who can help you use methods and protocols that centre your dog’s emotional wellbeing. Watch your dog’s body language to make sure your dog is having a good time.

You don’t need to be fluent in jargon to be a great dog owner, but a little understanding will help you make good choices over whom to trust and whether the methods you are using align with the kind of relationship you want to build with your dog – one built on trust, not fear.

Ready to build trust through positive reinforcement dog training methods? Train with me and learn how to support your dog with clarity and kindness.